by Adam Heardman via MutualArt

The reclusive Austrian symbolist’s dark, Schopenhauer-inspired drawings continue to shatter estimates. Here’s what you should know about Alfred Kubin.

Among the final writings of Arthur Schopenhauer is a collection of essays and aphorisms, the first of which comprises his thoughts ‘On the Suffering of the World.’ In his signature manner of subjective, personality-inflected philosophy, Schopenhauer begins: “If the immediate and direct purpose of our life is not suffering then our existence is the most ill-adapted to its purpose in the world: for it is absurd to suppose that the endless affliction of which the world is everywhere full…should be entirely purposeless and accidental.”

“Each individual misfortune, to be sure, seems an exceptional occurrence,” Schopenhauer observes, his tongue half in cheek, half clenched agonizingly between his sharpest teeth; “but misfortune, in general, is the rule.”

The general misfortune of all mankind has been the concern of certain visual artists who have, through observation of suffering and strife, lent colors and symbols to our understanding of the unendurable depths of human experience, and in so doing have seared themselves into our cultural consciousness. Artists like Francisco de Goya, Hieronymus Bosch, and Edvard Munch have achieved a timeless reputation because of their contributions to our syntax of suffering, our lexicon of bad luck, our parlance of pain.

Strange then, to come across an accomplished artist concerned with such themes who has at times fallen into a kind of obscurity (though he enjoyed some reputation as an illustrator and lithograph-artist in his own lifetime). As Schopenhauer himself says, “Not the least of the torments which plague our existence is the constant pressure of time, which never lets us so much as draw breath but pursues us all like a taskmaster with a whip.” Compared with certain other artists, Time the Taskmaster has, by turns, not been particularly kind to Alfred Kubin.

But if the art market is any kind of barometer, summer of 2019 suddenly represents the highest peak of Kubin’s influence and popularity - at the very least since an exhibition of his oils, watercolors, and drawings graced New York’s Galerie St. Etienne back in 1957. The catalogue for that exhibition admitted that it “took many years until Kubin’s strange and unconventional style found full recognition”, though in that year, the year of his 80th birthday, Kubin was maybe already considered “one of the great graphic artists of this century and one of its foremost book illustrators.”

His tenebrous star perhaps hasn’t shone as brightly since, until June this year. The Impressionist and Modern Sales at Sotheby’s on June 19 and 20 saw market highs for Kubin works. All sixteen of his pieces which came to auction over the two days sold, some of them doubling, tripling, or even multiplying by a factor of 8, their pre-sale estimates.

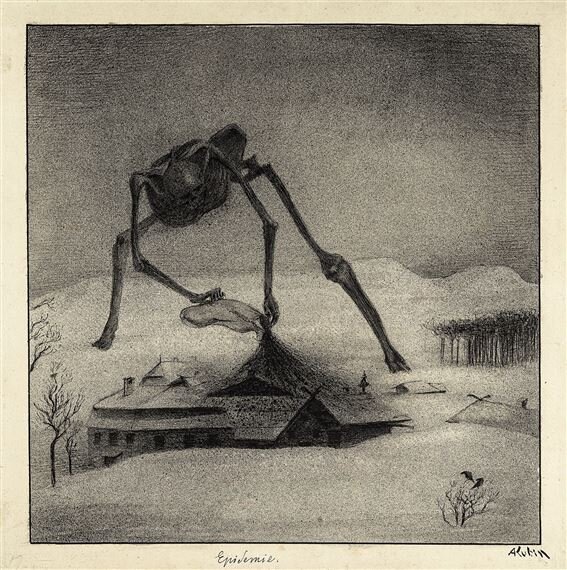

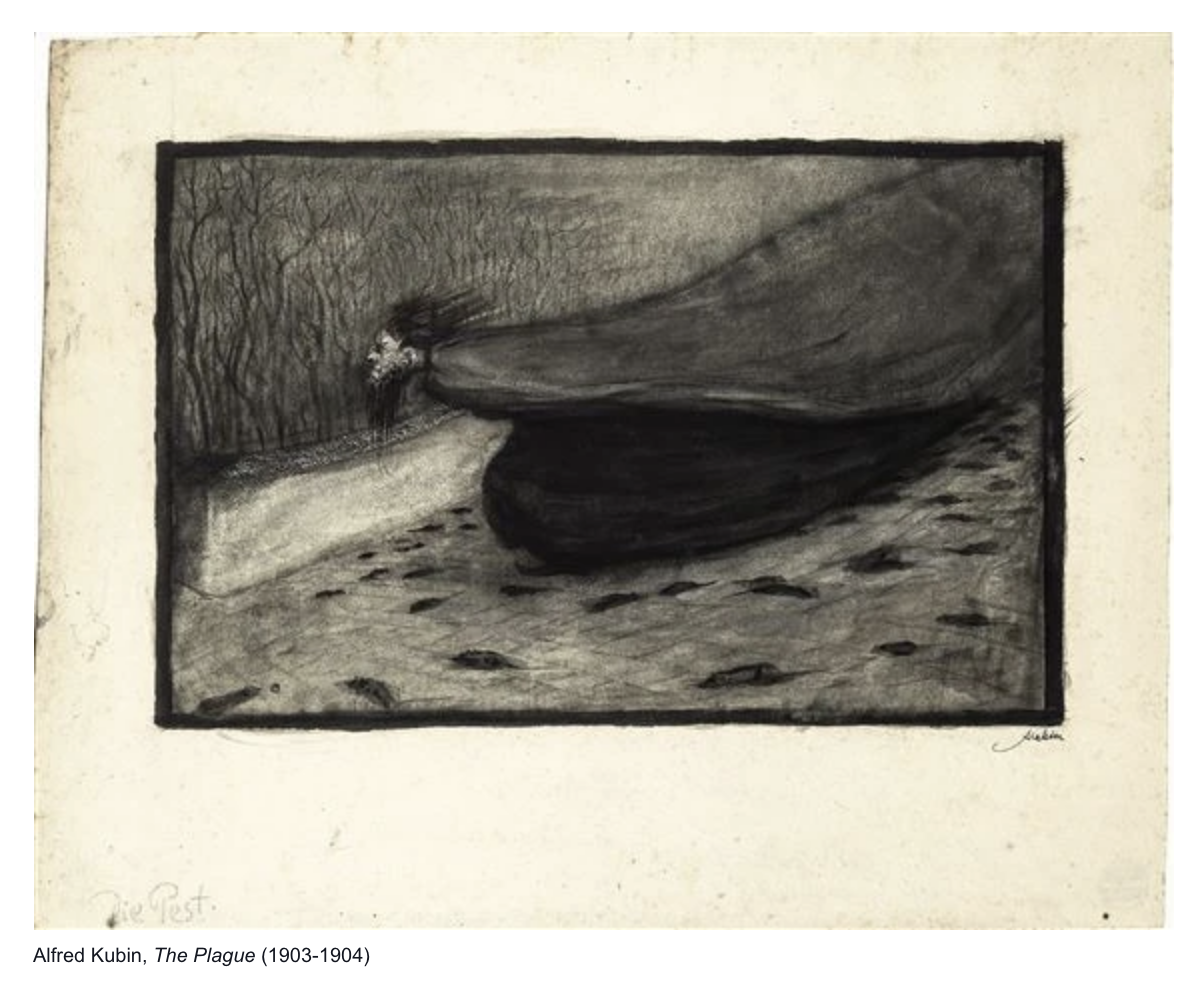

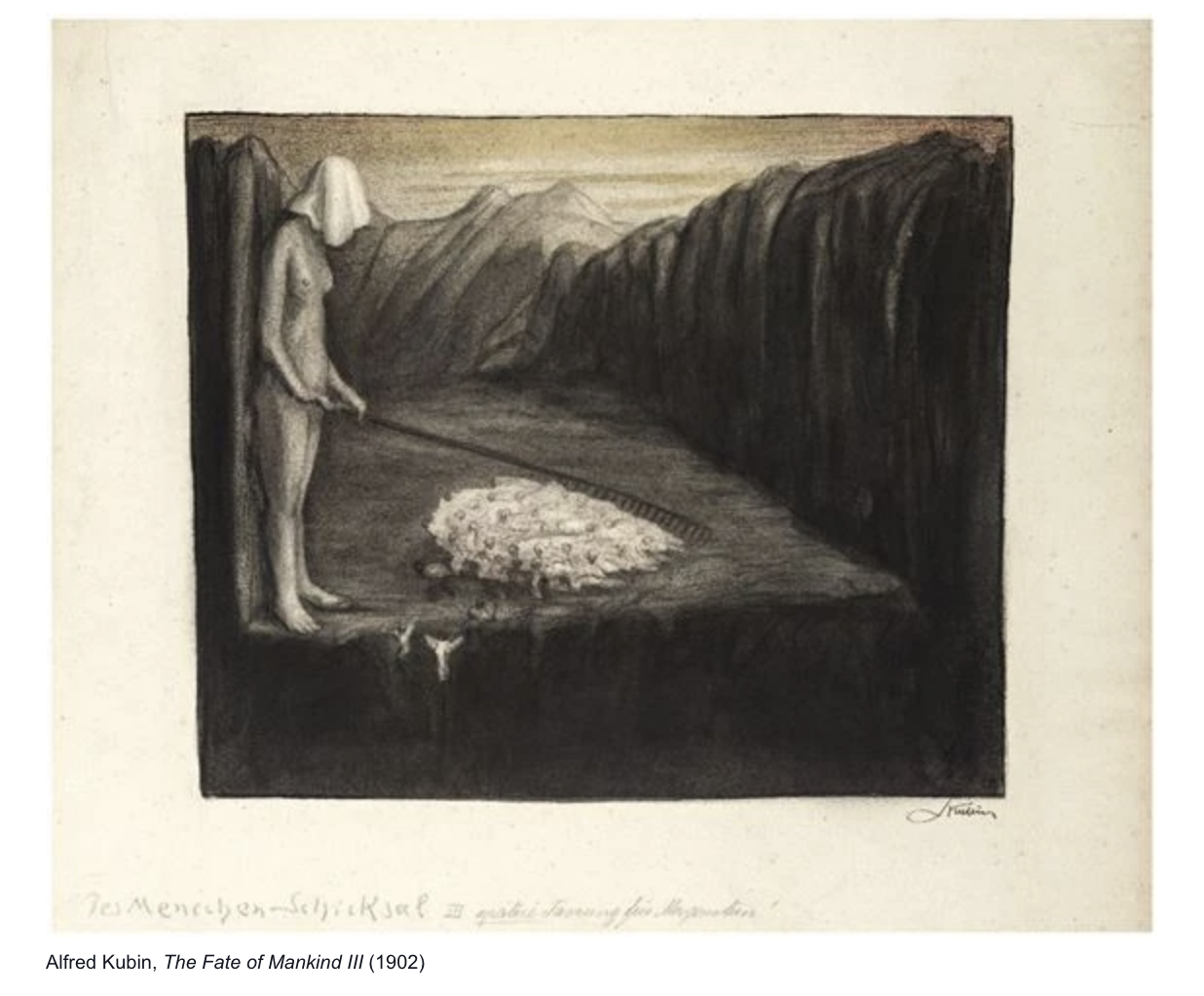

Epidemic (1900-1901) sold for £963,000 against a high estimate of £200,000. The Fate of Mankind III (1902) and The Hour of Death (1900) each raised £855,000 against high estimates of £120,000 and £150,000 respectively. The top performer against estimate was The Plague (1903-1904), which came to the Day Sale with a high estimate of £70,000 and sold for £579,000.

Strange then, to come across an accomplished artist concerned with such themes who has at times fallen into a kind of obscurity (though he enjoyed some reputation as an illustrator and lithograph-artist in his own lifetime). As Schopenhauer himself says, “Not the least of the torments which plague our existence is the constant pressure of time, which never lets us so much as draw breath but pursues us all like a taskmaster with a whip.” Compared with certain other artists, Time the Taskmaster has, by turns, not been particularly kind to Alfred Kubin.

But if the art market is any kind of barometer, summer of 2019 suddenly represents the highest peak of Kubin’s influence and popularity - at the very least since an exhibition of his oils, watercolors, and drawings graced New York’s Galerie St. Etienne back in 1957. The catalogue for that exhibition admitted that it “took many years until Kubin’s strange and unconventional style found full recognition”, though in that year, the year of his 80th birthday, Kubin was maybe already considered “one of the great graphic artists of this century and one of its foremost book illustrators.”

His tenebrous star perhaps hasn’t shone as brightly since, until June this year. The Impressionist and Modern Sales at Sotheby’s on June 19 and 20 saw market highs for Kubin works. All sixteen of his pieces which came to auction over the two days sold, some of them doubling, tripling, or even multiplying by a factor of 8, their pre-sale estimates.

As an illustrator, he has an eye for the emblematic. His symbols say no more than is necessary. They’re bold without being cloying. He draws with brevity but manages to unfold, in the suggested but unseen moments before and after his particular chosen frame, rich narratives that are as historical as they are personal.

Alfred Kubin, The Hour of Death (1900)

Schopenhauer, one of Kubin’s great influences, indulges in a kind of faux-disbelief at the purposelessness of suffering, in order to flip it around into a positive cognitive experience. Kubin observes a similar split between incredulity and faith. He revels in the accidents of association which allow for a symbolic language to arise, but is strangely disbelieving in their existence as mere accidents. This is a kind of negative path to faith, to magic. He, like Schopenhauer, is a sweet darkness, like treacle or liquorice. An acquired taste, for sure, but generally rich as a rule.

Much like Schopenhauer’s late-career aphorisms, and also, weirdly, much like contemporary internet memes, Kubin’s drawings operate as self contained units of cultural consciousness, presenting a narrative as rich as a Goethe story all at once in a single frame, in one image. Like a comet with its tail of light, their immediate form trails energy, historical significance, and emotional depth.

The Fate of Mankind III shows exactly Shopenhauer’s “taskmaster,” sweeping the living towards the cliff of their deaths. Though ‘master’ is a misgendered term here - the figure is a faceless but all-powerful woman. There’s a psychosexual element at play.

The Hour of Death shows Kubin’s philosophic imagination at its most ingenious. The scything hand of the clock beheads men as it turns, the severed heads caught in a net below. Though it’s horrifying, it cannot comfortably be said to be pessimistic. We delight in its creativity and ingenuity, even as we recoil from the graphic imagery and stark invocation of mortality. By turns we are repulsed and compelled, like with all the best horror.

Schopenhauer the philosopher is often said to have had the mind of a poet or artist, but the overwhelming achievements of his predecessor, Goethe, meant that he (and his near-contemporaries in German metaphysics) turned to philosophy as their imaginative outlet. Certainly, he takes a sort of monochrome delight in conjuring images, correlatives and metaphors to elucidate his theory of the metaphysical ‘will’ of the world. In the compulsive picture-making of the Austrian Kubin, many of Schopenhauer’s rhetorical imagery find its visual form.

Alfred Kubin was born in 1877 in the town of Leitmeritz. His mother died when he was young, and at the age of 19, Kubin attempted suicide at the site of her grave. His preoccupation with death began early, and developed through his experiences in the Austrian army and in his artistic practice throughout two world wars. It’s now well known that Kubin spent his entire life in Austria, and from 1906 until his death led a reclusive existence in a 12th Century castle estate, Zwickledt, in upper Austria. From here, he drew the phantoms and spectres that haunted Europe through conflict, strife, and the rise of fascism.

Alfred Kubin, Head of a Sick Man (1921)

It’s tempting, though worrying, to read in his contemporary significance some intimation of similar dark forces beginning to rear up in the fractious politics of the West. Schopenhauer talks metaphorically of the “torments that plague our existence.” Kubin draws The Plague manifest and embodied, sweeping down in an exponential curve towards a pock-marked ground, like the trend of a collapsing economy, or the menace of fascistic impulses, or literal sickness itself.

But the clamour for his works in the market is of course also influenced by the feeling of revelation whenever they do appear. It’s significant that the 16 works which sold last month were “restituted to the heirs of Max and Hertha Morgenstern.” Max was Kubin’s friend and great patron during his lifetime. He was a great and renowned collector of literature and art but was forced to leave behind many possessions when, as an Austrian Jew, he was compelled to flee to England in 1938.

His collection was looted severally, mostly by advancing Russian forces. In their appearance at auction after being restituted, these Kubin works gain an extra layer of pain-inflected revelation. The excitement of their rediscovery and return nevertheless conjure the darkness inherent in their initial loss. This atmosphere chimes well with the weird wisdom of the pictures themselves.

Each gouache or drawing which emerges feels like some precious insight into the human psyche, or a dark slice of illustrated history wrested from the gothic seclusion of Zwickledt.

The performance of this most recent and most significant collection of Kubin works at auction confirms his strange power, and suggests a robustness to his reputation. He’s a divided figure - by some metrics almost wildly popular, but retaining an air of mystery, evasiveness, and intrigue. Through him, we can discover the compulsions of our darker zones. But maybe we find it difficult to look too long or too directly into such spaces. Perhaps we love and are horrified by Kubin because he knows what Edgar Allan Poe (whose works he famously illustrated) knew, and shows it to us unflinchingly: “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?”

.